CLEARING OUT THE OASIS

by Bill Griffith

ROADSIDE MAGAZINE, June 1998

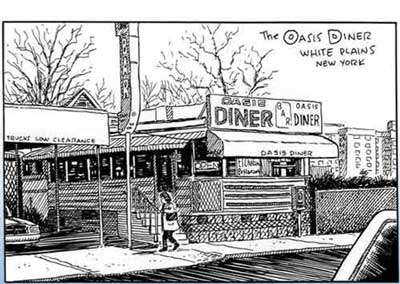

It started out innocently enough. I needed detailed photographs of diners. Specifically, I needed photos of the interiors of diners, of people sitting on stools at the counter, eating and talking. A few months back, in my syndicated daily comic strip, "Zippy", I’d begun a series of strips featuring "Bert ‘n’ Bob", two seriously committed diner patrons. Bert ‘n‘ Bob love diners. Bert ‘n’ Bob live diners. Bert ‘n’ Bob are diners. Zippy himself makes an occasional appearance in these strips, but more often it’s Bert ‘n’ Bob on their own, ruminating on life over coffee, rice pudding and the Daily Special. The diner books in my reference library contained mostly exterior shots; interior scenes were rare. My models for Bert ‘n’ Bob came from a single photo I took in Collins Diner in Canaan, Connecticut, on a trip in July, 1997 (great lemon meringue pie). They’re seen in a three-quarter rear view, a pose by now quite familiar to my readers. Though I was enjoying the repetitive, eerily existential quality of that one view, I finally grew weary of it. And, thus, I found myself in the Oasis Diner in White Plains, New York, early in February.

by Bill Griffith

ROADSIDE MAGAZINE, June 1998

It started out innocently enough. I needed detailed photographs of diners. Specifically, I needed photos of the interiors of diners, of people sitting on stools at the counter, eating and talking. A few months back, in my syndicated daily comic strip, "Zippy", I’d begun a series of strips featuring "Bert ‘n’ Bob", two seriously committed diner patrons. Bert ‘n‘ Bob love diners. Bert ‘n’ Bob live diners. Bert ‘n’ Bob are diners. Zippy himself makes an occasional appearance in these strips, but more often it’s Bert ‘n’ Bob on their own, ruminating on life over coffee, rice pudding and the Daily Special. The diner books in my reference library contained mostly exterior shots; interior scenes were rare. My models for Bert ‘n’ Bob came from a single photo I took in Collins Diner in Canaan, Connecticut, on a trip in July, 1997 (great lemon meringue pie). They’re seen in a three-quarter rear view, a pose by now quite familiar to my readers. Though I was enjoying the repetitive, eerily existential quality of that one view, I finally grew weary of it. And, thus, I found myself in the Oasis Diner in White Plains, New York, early in February.

Camera in hand, I entered the Oasis on a Sunday afternoon accompanied by my wife Diane and a friend, Chad. Though an almost perfectly preserved early fifties diner, the place had been transformed recently into the "El Chalan Restaurant", serving Latin-American fare. The booths were full, so we sat at the counter. The patrons looked to be largely Hispanic. Hopes for lemon meringue pie dashed, I scanned the menu and ordered a bowl of Sopa de Pollo. The joint was humming. Salsa music blared from the jukebox. Valentine’s Day posters and festive red balloons hung from the walls. Families, couples and single diners were all enjoying their Sunday afternoon, chowing down on spicy shrimp, Enchilladas Suizas and big bowls of steaming chicken soup. A booth at the far end opened, so we moved in, a perfect vantage point for picture-taking. My soup arrived. More like a rich stew, it was delicious. I took my first picture, a nice perspective shot of the patrons at the counter. After the flash went off, one or two people turned to look at me, a standard response. Taking pictures in public places is always a tricky proposition. Some people take it in their stride, others give you that "Hey, what are you up to?" look. I got up and took a few more shots of people at the counter and the booths. I was getting just what I needed. Visions of future multi-angled poses of Bert ‘n’ Bob filled my head. I dug into the soup and asked Chad how he was enjoying his shrimp dish. "Awesome", he said, between mouthfuls.

Diane was the first to notice. "Why are so many people leaving?", she asked. "I don’t know", I said, "maybe it’s just the usual ebb and flow." Diane was not convinced. "I think they’re leaving because you’re taking pictures of them", she said. "No way", I responded. I took a few more shots. The diner’s owner approached our table, a look of concern on his face. "Can I ask you why you are taking pictures?", he asked me. "Uh, well, you have a beautiful diner-- I really like diners", I answered lamely. "Hope you don’t mind." The expression of concern on his face turned to one of worry. He walked away. "What was that all about?", I said to Diane and Chad. "You’re making the people in this place nervous," Diane said. "You’re a guy in an overcoat with a camera. They probably think you’re from immigration."

"Me? La Migra?", I said. Little by little, in ones, twos, and threes, the place emptied out until there was no one in the diner but the owner, two waitresses, and Diane, Chad and me. Denial wasn’t working. It was obviously my fault. I had cleared out the diner. In my harmless quest to document diner interiors, I’d lost the owner of the Oasis Diner a couple of hundred bucks in Sunday dinner receipts.

I got up and shame-facedly paid the check and we shuffled out of there. Chad’s parting reassurance to the owner that I "really just like diners" didn’t quite cut it. We got in Chad’s Jeep and drove off.

The next day, visiting friends in Brooklyn, I told them my tale of humiliation and guilt. Clearly, I needed a way to deal with this situation if it came up again. After all, the Oasis was just the first of many diners I planned on photographing. And quite a few of them have morphed into various ethnic restaurants while retaining their dinerness. The same thing could happen again. I needed a more plausible (and more reassuring) reason to give the next concerned owner. "Tell ‘em you’re a reporter doing an article on the greatest diners of the tri-state area", somebody suggested. "No, say you’re doing a photo layout for Esquire", volunteered another. But no one came up with a sure-fire cover story. Suddenly, a light bulb appeared in a balloon over my head.

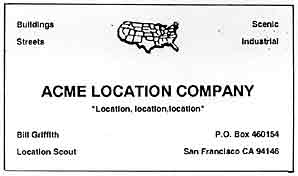

"I’ve got it!", I shouted. "A location scout! I’ll tell them I’m a location scout for a Hollywood movie studio and their diner might be just what they’re looking for! The movies! Hollywood! Who can resist stardom?"

Everyone agreed it was perfect. But how would I convince a doubting diner owner I really was a location scout? "You need a card", someone said. "There are copy shops in midtown Manhattan that have these instant business card machines. I think it’s five bucks. You do it yourself."

END